Money and Mental Health: What more can we do?

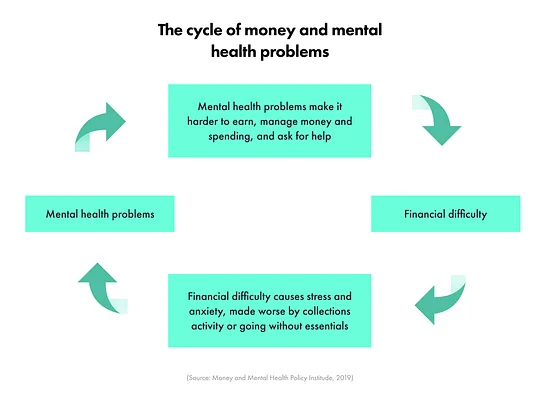

The link between poor mental health and money worries is well-known, as is the fact that all too often it can become a vicious circle.

Poor mental health can lead to poor financial health and vice versa, trapping people in a never-ending spiral where one problem continually exacerbates another. To drive that home, across England more than 1.5 million people are experiencing both problem debt and mental health problems, according to Money and Mental Health.

In the UK both subjects have received an increasing volume of column inches recently, something that has been driven by any number of factors but not least ongoing political austerity policies and the uncertainty caused by the protracted Brexit process.

Why are the two so intrinsically linked?

86% of people who experience mental health problems said that their financial situation had made their mental health problems worse, according to a survey by Money and Mental Health.

Worry about debt is one of the most common triggers for the exacerbation of mental health problems, a situation which can be made worse by the aggressive or impersonal behaviour of debt collectors — whether they are informal loan sharks or large financial institutions. Additionally the current trend of showing customers as much data as possible about their finances, while helpful for many, can cause or exacerbate anxiety-related conditions.

At the same time, those with mental health problems are more likely to struggle with managing their finances, particularly if their illness means they need to take time off work, find it harder to make financial decisions or are in a pattern of spending to make themselves feel better.

Further, poor mental health that impacts a person’s ability to carry out day to day activities can result in costs of £1,100 - £1,550 a year, due to inaccessible services, poor regulatory protections and inadequate support according to Citizens’ Advice.

Financial institutions do not, generally, have a history of managing situations where a customer is struggling with finances due to mental health problems well. Much of the time this is not intentional, but due to a failure to understand the situation.

Banks and lenders, as a rule, are not able to spot patterns in a customers’ finances which may indicate an underlying mental health problem, nor do they make it easy for customers to inform them of their illness, assuming they are willing or able to do so. Even if a particular staff member is empathetic their ability to act is typically hamstrung by processes and red tape as illustrated by this example from Mind.

What are financial services companies doing to help?

UK banks are starting to wake up to the situation, and some are making steps towards easing the issue for affected customers. I’ve highlighted a few examples below but it should be noted that this list is not exhaustive, and that nearly all banks have vulnerable customer support teams or trained staff.

Barclays has an easy to find Mental Health support page on its website and allows customers to block their card being used in certain types of retailers to help manage spending. In terms of specific services for those with mental illness, it offers longer branch appointment times, private rooms and the attendance of a companion at meetings. But customers still have to proactively reach out to the bank, and for many very unwell people that will be impossible if they suffer from avoidance or disordered thinking.

Monzo uses plain language in all customer communications, gives customers control over which notifications to receive, allows them to set budgets, opt out of lending at the point an account is opened and turn off lending promotions.

It also allows customers who are struggling with debts and their mental health to “take a break” from communications about their debt while they focus on their recovery. While some of these features and services are innovative, they do still rely on the customer being able to make decisions about their finances.

Nationwide’s Open Banking For Good Challenge features two fintechs which are specifically targeting the money and mental health issue.

- Toucan, which is still in development, offers a service which is the opposite of many personal financial management tools. Instead of displaying lots of information about a customer’s financial situation, it simplifies the picture, showing only a financial “status update”. It also enables users to set up alerts to be sent to someone they trust when their balance gets low or when spending is higher than normal. That means another person knows about their situation, without the user having to approach them. It has the backing of the Money and Mental Health Charity so it will be one to keep an eye on at launch.

- Tully, which is accepting applications for early access, consolidates a user’s financial accounts and then provides them with a realistic budget. If the user is struggling with debt, Tully offers to speak to lenders on their behalf and try and arrange “breathing space” while creating a personalised repayment plan. A product designed specifically for those worrying about money, Tully is meeting a clear need in the market. However, the fact that it is app only means some more vulnerable people will likely struggle to use it.

What is left to do?

The short answer is: a lot.

Initiatives and products like those mentioned above are still rare, and most rely on technology to help people — which still leaves a huge swathe of consumers that they won’t be able to reach.

For example, 51% of people with mental health problems receive paper bills from 1 or more utility supplier and 18% use cash or cheques to pay bills in order to help them manage their money, according to Citizens Advice. For this group, apps and online services will be of limited use.

There needs to be more widespread change in the financial services industry. The practice of offering “breathing space” should be standard, and awareness of and access to vulnerable customer support teams should be raised.

Additionally, with the increasing use and reliability of machine learning techniques, I would hope financial firms are investing in solutions that help them proactively detect when a customer may be struggling with their mental health and looking for appropriate ways to act in response.

I look forward to seeing more activity in this space as financial services firms prove that they really do have their customers’ best interests at heart.

If you have been affected by anything this blog mentions, you can find a wide range of support at Mind, Citizens’ Advice and Rethink.