11:Years – The Past, Present & Future of UK Fintech

Introduction

12 years ago there was a crisis in the subprime mortgage market in the US. One year later, investment bank Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy. These events marked the start of what has become known as the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–8.

11 years after the shock of the fourth largest investment bank in the US folding, we’re still scarred by the impact of that crisis. Today, consumer sentiment towards most financial institutions remains lukewarm at best, and people are, in many cases, still far worse off financially than they were 15 years ago. But as so often happens in unstable and uncertain times, there were those who saw it as an opportunity, in this case, to reimagine what the financial services industry could be and do.

Regulators, entrepreneurs, technologists and investors set about solving issues that had been brought to light, exacerbated and, in some cases, created by the financial crisis. This was particularly true in the UK, and more specifically London, where a world-leading fintech ecosystem emerged.

However, we are now at another turning point as the UK moves towards leaving the European Union (EU). While we don’t yet have the details of what’s known as Brexit, we do know it will create upheaval across England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales and likely across the EU too, including in the financial services industry.

This report will examine the drivers for the emergence of the UK, and London specifically, as a global fintech hub – namely the regulatory changes that occurred in the region as a direct result of the crisis, and the ways in which those changes encouraged the unleashing of talent and the inflow of investment. I will also explore what’s likely to happen next now that leading status has been achieved, but the future is once more far from certain.

How did we get here?

Regulatory change

One of the biggest drivers of change in the UK financial services industry post-financial crisis was regulatory reorganization – and the first step towards a new regulatory regime was the dismantling of existing bodies and the founding of new regulatory entities.

The Birth of the FCA and the PRA

Between 1997 and 2013 the Financial Services Authority (FSA) was the dominant regulatory body along with the Bank of England (BofE). Then in 2010, in the midst of the crisis, the Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne decided regulatory reform was needed to make it clearer who was in charge of overseeing which parts of the industry and in turn, prevent any more failed banks and government bailouts. As part of that reform, the prudential and conduct operations of the regulator were split into two different organizations in 2013.

The Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), which is part of the Bank of England, is in charge of creating and enforcing policies that ensure financial institutions are safe and secure businesses that operate with the least possible chance of getting into financial difficulty.

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is in charge of ensuring consumers are treated fairly by financial institutions, a remit that includes encouraging competition in the industry. Its role is also to ensure the integrity of the UK’s financial system, something that was widely felt to be much-needed in the post-crisis world.

Focus on the FCA

The PRA and the FCA, along with the BofE (which saw its remit grow after 2013) worked together to push through changes in the financial services industry, but arguably, the FCA has had the largest involvement in the development of fintech.

An unusual mandate

The FCA is unusual among global regulators in that its mandate explicitly includes the promotion of effective competition in the interests of consumers. That means it has a greater motivation to promote and foster innovation than many of its peers.

Project Innovate

One of the major ways in which the FCA adheres to its mandate is through an initiative called Project Innovate which was started in 2014.

FCA Innovate has six ways in which it tries to help firms that are looking to compete in the industry achieve success.

1. Direct Support

One of the first initiatives to go live, Direct Support, contributed to the creation of the Regulatory Sandbox. It offers, “tailored regulatory support for innovative firms” and eligible firms can receive a number of different types of support via a dedicated contact. If the FCA decides that a firm needs to apply for authorization or a variation of permission, it will help that firm prepare an application. Once authorized, the firm will continue to receive support for the regulator for one year.

The feedback from those firms that had received direct support early on was that they also needed “to understand...whether [their] proposals are commercially viable, economically feasible, and…[they] would love to find a way for you, as a regulator, to support us in some form of testing”, according to Nick Cook. Consequently, the Direct Support function informed the creation of, and now works in collaboration with, the Regulatory Sandbox.

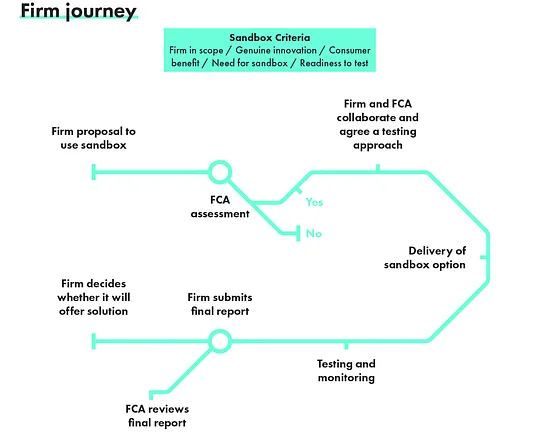

2. Regulatory Sandbox

Perhaps the most well known of the initiatives, the Regulatory Sandbox “allows businesses to test innovative propositions in the market with real consumers”. It is open to both authorized and unauthorized firms, as well as technology companies, and aims to provide participants with:

- The ability to test products and services in a controlled environment

- Reduced time-to-market at potentially lower cost

- Support in identifying appropriate consumer protection safeguards to build into new products and services

- Better access to finance

The success of the sandbox has surpassed the expectations of those who set it up, both in terms of the number of firms wanting to participate, and what the regulator itself has learned in the last 5 years. The sandbox has reduced the time it takes a firm to get authorized by around 40%, according to Chris Woolard.

The result is that the concept has been imitated in numerous other jurisdictions around the world. By the end of 2017, there were 20 live and proposed sandboxes in countries extending from Canada to Australia, and from Abu Dhabi to Hong Kong.

3. “GFIN”

GFIN is short for Global Financial Innovation Network, which was originally intended to be a global, or international, sandbox. It resulted from the success of the Regulatory Sandbox and feedback from firms saying that while the initial program was helpful, they would also find it useful if they could test in more than one jurisdiction at a time in order to scale more easily.

Now, GFIN is made up of 38 institutions, from different jurisdictions, some of which have a sandbox facility, and all of which have some kind of innovation support function. GFIN focuses on cross-border testing, as well as sharing insight, information, intelligence and ideas around new innovations in different markets, and how regulators are responding to those – to paraphrase Nick Cook.

GFIN’s first initiative is a pilot enabling selected firms to test new technologies in multiple jurisdictions at the same time. GFIN’s members are now working with 8 firms to develop testing plans and as and when those plans are deemed suitable, the firms will then be able to move onto the pilot testing phase. GFIN is still in its early stages, but its rapid movement goes to show how much demand there is among regulators to engage with fintechs and make it easier for them to succeed.

4. Advice Unit

As part of a drive to make it easier for consumers to access affordable financial advice, the FCA launched its Advice Unit, which “provides feedback to firms developing automated advice and guidance models”. Firms in the investment, pension, protection, mortgage, general insurance and debt segments that meet the set criteria are given regulatory feedback on their model. Additionally, firms that want to provide guidance (defined differently to advice under UK regulation), and those that are not authorized or seeking authorization, are also eligible to receive advice.

The Advice Unit has been a major driver of an increasing number of propositions coming to market that aim to make access to financial advice affordable and accessible to a much wider range of consumers than was historically possible.

5. Regtech

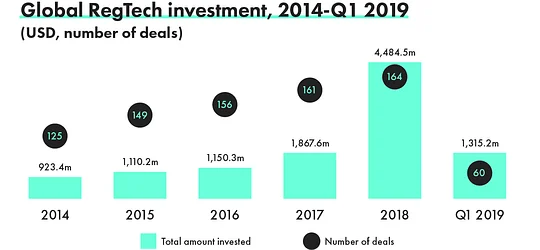

Regulatory technology is used by both financial service providers and regulators and it’s a booming segment. In order to capitalise on this, FCA Innovate’s regtech unit aims to encourage the development of technologies in this space.

Regtechs are accepted into the Regulatory Sandbox and can receive direct support, but the FCA also has two dedicated Regtech workstreams. The first is Digital Regulatory Reporting, in collaboration with the BofE and a number of other organisations, which is exploring how technology can improve the way firms submit their regulatory reports. The group is currently in a second phase of a pilot, working towards a goal to make lives easier for firms and their clients, as well as regulators. The second workstream is the hosting of a series of Techsprints where invitees explore the potential of new technologies and processes in a range of regulatory areas.

Source: Fintech Global

6. Engagement

To ensure its initiatives are helping the widest possible pool of fintechs, the FCA engages with firms across the UK and internationally. As part of its intent to develop fintech hubs outside of London, it is holding regional regulatory “surgeries” where innovative firms can address specific questions to representatives of the regulator face to face. This is important to the development of the nation’s fintech industry to ensure it has maximum impact across jobs, the economy and consumers – especially as the financial services industry has historically been centered on London.

International engagement comes partly in the form of Co-Operation Agreements with regulators in other jurisdictions such as Australia, Hong Kong and Singapore (among others). One element of these agreements is allowing fintechs to receive a referral from their home regulator, the FCA, and vice versa, designed to speed up the process of scaling internationally.

New Bank Licensing Regime

In 2013 the PRA lowered the initial minimum capital requirements for small bank license applicants to £1 million (or €1 million - whichever is higher). Its aim was to encourage the launch of new banks into the stale UK banking market.

In combination with a regime which allowed “restricted licenses”, it worked. Since 2010, 18 new UK banks have been granted, and held onto, banking licenses.

Restricted licences allowed the new banks, a number of which were digital-only, to operate with a restricted volume of customer deposits (and therefore real customers) while they iterated their technology and accrued more capital. The fact that the new banks were allowed to work with real customers while they fine-tuned their systems and products, played a major role in the success of these banks at launch, as they knew they were offering products and services that customers wanted and needed.

Then, in 2016, the New Bank Start-Up Unit launched as a partnership between the PRA and the FCA, and further encouraged new competition in the UK financial services market. It provides information and support to companies looking to start a new bank in the UK, and helps guide them through the licensing process.

The success of the UK regulators in encouraging new banks to enter the market has spurred regulators in other markets to follow similar patterns and has resulted in new banks, particularly digital-only banks, cropping up all around the world.

What’s likely to happen next?

The UK’s forward-thinking approach to regulatory change post-financial crisis, which continues today, was a significant driver in the emergence and continued development of a thriving fintech ecosystem. Entrepreneurs finally had a way to test their ideas in an environment that wanted them to succeed, and the result has been mostly positive on the financial services industry as a whole.

But as political uncertainty continues, what is going to happen to the UK’s regulatory regime next?

The UK is likely to continue following the regulatory regime of the EU closely, allowing as many firms to continue operating across both jurisdictions as possible. That said, many firms are currently authorized by a single regulator but operate across the EU under a system known as “passporting”. That means that a large number of UK authorised firms are seeking new authorization in an EU country, and vice versa, to ensure they can continue to operate in their current fashion. This consumes significant resources, perhaps too much for some startups, and creates the potential for firms to fall foul of differences in the rules associated with authorization in different countries.

The UK’s Cooperation Agreements with countries outside the EU are unlikely to be affected, in fact, the most recent agreement with Australia specifically says ties will be strengthened post-Brexit. The FCA will also want to sign more Cooperation Agreements with new jurisdictions to ensure the UK fintech ecosystem maintains links with like-minded hubs, providing a way to share knowledge and ensuring UK firms have a range of options should they choose to scale internationally.

Overall, it’s unlikely the UK’s regulators will change their approach to fintech and innovation as a result of Brexit. They have established a regime that is working so well it’s being copied, and imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Additionally, the regulators have adopted an iterative approach, adjusting and adapting as they learn – that will also stand them in good stead. So, continuity at least in support and guidance should be assured, if not in regulation and legislation itself. In turn, that will reassure both firms that are already operating in the UK and those that are looking to the region as an expansion market.

Fintechs Take Advantage

The shift in the UK’s regulatory environment was a major contributor to the emergence of the region’s fintech ecosystem following the financial crisis. However, there were several other key elements that also came together to create the perfect environment, which enabled UK fintech to flourish in the way that it has over the last decade.

New Ideas and First Mover Advantage

One of the essential components of any successful business is to ensure you are providing a solution to a problem.

Technology that could enable lower cost, digital-only products and services in the financial services industry was well established and widely available before the financial crisis, but its aftermath meant there was now additional customer demand and regulatory support for them. Fintech entrepreneurs and would-be entrepreneurs jumped at the combination of factors that meant they could now create solutions to new and existing issues.

New Ideas

Some of the biggest and well-known fintechs in the UK today were formed as a direct result of ideas sparked by the events of the financial crisis and its effects.

New ways of doing things

Worldremit, TransferWise (remittance firms) and Funding Circle (an SME marketplace lender) were all founded directly after the financial crisis in 2010. They saw opportunities to capitalise on customer disillusionment with, or abandonment by, the financial services establishment by offering up new ways of doing things. By avoiding branches or brick and mortar stores, building core systems from scratch using the latest technology, and trying out unusual or entirely unique business models, they offered customers solutions to problems at more attractive prices than the banks could or would offer them.

Some of the earliest customers of these firms were forced to look for alternatives as banks would no longer service them, particularly in the case of SMEs, but others were looking for alternatives to bank products as a way of expressing their dissatisfaction with the industry. Zopa, a consumer lender, had been founded before the crisis but really took off once the consequences became apparent.

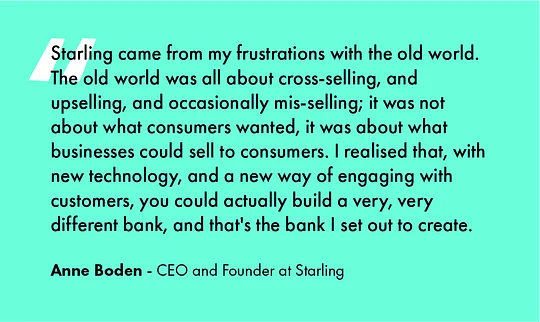

Digital-only banks

The first fintechs off the mark focused on solving one customer problem in the most effective way possible, but others chose a longer game, believing they could rival the incumbents in multiple areas. Starling and Monzo began in 2014 and 2015 respectively, their founders disillusioned with the way big banks were doing things and spurred on by the regulatory changes that had been implemented, to bring their ideas about new ways of doing things to fruition.

New ideas in the field of banking included; digital-only banks, with no branches or even contact phone numbers, the ability to open an account using nothing but a smartphone and ID, real-time alerts to let customers know money had entered or left their account (even though that money wouldn’t actually move until one or two days later), automatically categorizing a customer’s spending, in-app card freezing (and unfreezing), and communicating with customers in an entirely different tone of voice. Some of these ideas may have been considered inside legacy institutions previously, a few may even have been trialed, but it took until the early 2010s for them to all come together.

Many of these ideas were inspired by the likes of Uber and Spotify, which followed on from Google and Facebook in providing intelligent solutions to real-world problems in ways that chimed with the way customers lived their lives.

First Mover Advantage

After the crisis early UK fintechs took advantage of the new market conditions that helped form the basis of the UK fintech ecosystem as we know it today. So why didn’t the industry incumbents, with their large customer bases, access to significant resources and well-known brands act to prevent these newcomers from getting traction?

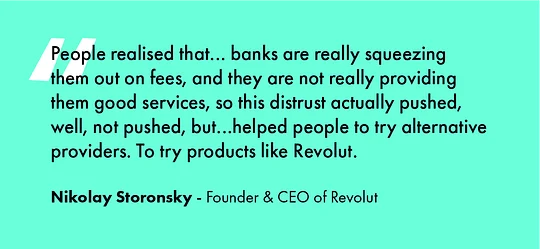

Banks lost customer trust

Many people felt betrayed by the incumbent banks – prior to 2007/8 they may not have thought these organisations were working in their best interests, but it occurred to few that they might actually be working against them. The UK saw a run on a bank (Northern Rock) for the first time in over 100 years as people no longer trusted in its ability to return their deposits, banks stopped lending, leaving SMEs particularly vulnerable, and organisations that considered themselves “too big to fail” were bailed out to the tune of billions of pounds of taxpayers’ money. No wonder people started looking for alternatives, and more importantly for alternatives that could show they put the customer first. It was going to take significant time for the incumbents to win back some, if not all, of that trust and in the meantime, the startups had stolen a march on them.

The disadvantage of a legacy

Aside from a decline in customer demand for their services, incumbents were also hamstrung by their legacies. The startups could move quickly, with no technical, product or process debt or culture to bog them down. They saw an opportunity and took it, with technologies such as cloud-computing and APIs as their base, they built products and services using new ways of working such as small teams that worked on projects rather than in strict teams. This approach, along with the decision to avoid bricks and mortar branches, enabled them to run much more lightweight organisations that could move faster, with lower cost bases and therefore lower fees. The fintechs launched bare-bones products and adjusted them within days or weeks, responding to users’ feedback and ensuring that what they were building was what customers wanted and needed. All of which was impossible for the incumbents to replicate swiftly, again giving the startups a significant first-mover advantage.

What’s likely to happen next?

The success of a number of fintechs founded post-crisis will act as inspiration for budding founders, particularly in the current political and economic climate. If these fintechs did well out of a particularly perilous situation over 10 years ago, then why shouldn’t others follow in their footsteps today?

The reasons why they should include the beneficial regulatory environment outlined above which has matured since the first changes were made and now provides one of the most supportive environments in the world. The fact that so many people are now used to doing most of their day-to-day activities on their smartphones and other devices will also work in entrepreneurs’ favour when it comes to implementing new ideas.

However, entrepreneurs should be wary of simply piling into a crowded market – one of the most important factors in TransferWise et al’s success was the originality of their idea and the fact that it solved a significant customer pain point. In the current UK market, it would make more sense to look around at the wider financial services ecosystem, where everything from mortgages to credit cards is starting to be disrupted and look for a gap there, rather than trying yet another take on the current account. In fact, we’ve written another report detailing how one might enter a new banking market in today’s climate which you can find here.

Talent

Once you have demand and a solution, you need people to help you make it happen

London has been a financial centre for centuries and that’s meant a hugely diverse and experienced talent pool has evolved in the city. That talent has come from other areas of the UK, as well as the rest of the world, attracted to the city by the fact it’s the hub of not only finance, but also most other services industries, the government and regulators.

Additionally, the UK’s size means London is close in proximity to some of the world’s best universities, including Oxford and Cambridge, as well as being the home of institutions that specialize in subjects such as business and technology, like Imperial College. The reputation of these establishments means they draw students from all over the world, many of whom decide to stay on after their studies have finished and make the UK their home – even if only for a few years.

That said, this has been the case for a long time, so why did so many of these talented people suddenly decide to turn their hand to starting their own companies or go to work for nascent businesses with uncertain chances of success? How did talent become one of the major building blocks of the UK’s fintech ecosystem?

The Crisis as a catalyst for unleashing talent

The financial crisis triggered a number of factors that encouraged people to take a chance on a burgeoning industry.

The impact of widespread job losses

At the most basic level, more talent was available. Large numbers of people working in financial services lost their jobs throughout 2008 and 2009 – the final figure is estimated to be around 45,000. A significant proportion of those job losses came from the investment banking industry, which might go some way to explaining why many of the UK’s earliest fintechs were started by entrepreneurs with investment banking backgrounds.

At the same time, people starting their careers had far fewer opportunities to enter the investment banking world, driving them to look elsewhere.

Those graduates who might originally have gone into investment banking and stayed there for their entire careers ended up taking a different route. Many of them went on to put what they learned at those consultancies to use elsewhere – starting their own fintechs or, having learned about the burgeoning ecosystem while at a consultancy, going to work for fintechs, further stimulating the development of the industry.

Disillusionment

If you listen to fintech founders talk about their reasons for starting companies in this space, many of them will say that the financial crisis was the wake-up call they needed to realise how badly the financial services industry treated many of its customers. For some founders, it was the last straw while for others the reaction to the crisis by many of the big banks compounded the problem to the point they felt compelled to act.

In my time in AIB, we managed to make huge progress, but it was pitiful, going out to towns and villages across Ireland, and hearing what businesses and consumers were saying about the industry. I was ashamed to be a banker. I knew things could be better.

Anne Boden, CEO and Founder of Starling

This is especially true if you look at some of the first fintechs to make their mark in the UK in the wake of the crisis – particularly lenders like Zopa and Funding Circle. Both firms spotted opportunities to serve customers either side of the balance sheet equation (borrowing and lending) who were being left behind as the banks sought to stabilise their own businesses and balance sheets, to the detriment of customers. The crisis and its fallout spurred the founders to think outside the box and provide solutions to real problems.

At the same time, that disillusionment that drove fintech founders on also had an impact on the people who agreed to go and work for those founders in the early days. Instead of going into banking, many graduates felt compelled to work for a firm that hadn’t been caught up in the causes of the crash. The same can be said for those who had retained their jobs within the legacy financial services industry and still took the chance to move onto a smaller firm, likely on less money and certainly with less job security.

What’s likely to happen next?

The financial crisis stimulated the development of the UK’s fintech ecosystem by unleashing talent that was able to create innovative solutions to widespread problems. It also provided a stimulus for that talent to want to go down the route of starting a firm or working for a small company in a nascent industry. The question is, all these years on, is that talent going to dry up and put the brakes on the further development of the UK’s fintech ecosystem?

The answer is unclear. The UK has, like many other fintech hubs, more demand for talent than supply can meet. That’s particularly true for roles that require technical specialism or that didn’t exist 10 years ago, such as data analysts, AI specialists and digital product designers. Back in 2017, almost 60% of UK fintechs said that attracting suitable talent was their biggest challenge (higher than driving adoption or raising capital) and that is unlikely to have declined. The UK’s departure from the EU won’t help matters here, as has already been mentioned a large number of fintech employees in the UK are citizens of other countries and up to a fifth from them hail from the EU. Some of that talent won’t be able to stay on after Brexit, some of it won’t want to.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. There are many initiatives underway designed to ensure UK-based fintechs can continue to access the talent the industry needs to thrive and grow.

Some fintechs have taken the lead themselves, Spotcap’s Fintech Fellowship offers up to £8,000 towards the cost of an MSC or MBA in a fintech-related field for one student each year, for example. At the same time, educational establishments are increasingly offering fintech-specific courses which should also stimulate home-grown talent, especially as the next generation of students are highly likely to be fintech users and therefore aware of it as an industry and willing to explore it as a career path.

Government tax incentives (e.g. Entrepreneurs’ Relief which was first introduced in 2010 in the wake of the crisis) are also designed to encourage entrepreneurship, which should continue to stimulate the flow of new companies entering the industry.

Amid all the above it must also not be forgotten that the UK fintech ecosystem remains one of the best established and most vibrant in the world, and that alone will be enough of a pull for some. In the short run, things look uncertain, but ultimately it seems likely that the UK fintech ecosystem will find a way to secure the talent it needs.

Investment

The next ingredient, after an idea and a team, is money.

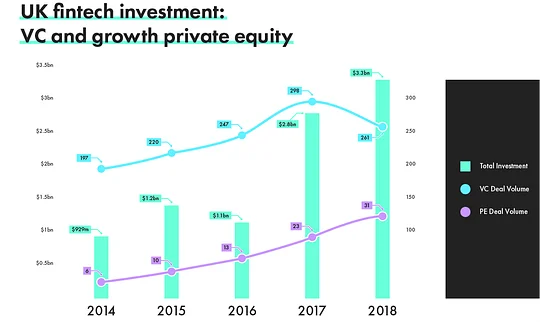

The UK fintech industry attracted nearly £3 billion in investment in 2018 according to one source, and it wasn’t the first time annual investment had been in the billions. Investment in UK fintech now flows from all over the world and from a range of sources including Private Equity, Venture Capital and Corporate Venture Capital among others, but how did we get here?

Investors Take Notice

Numerous factors contributed to the increased interest in fintech from investors of all sizes in the years following the crisis.

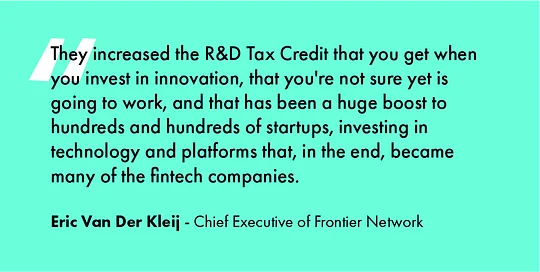

Tax incentives encouraged investment in startups

A number of government tax incentives boosted the flow of money coming into startups from smaller investors, many of whom were affluent individuals (known as Angel investors).

1. EIS and SEIS

The EIS (Enterprise Investment Scheme) is designed specifically to encourage investment into startups and early-stage businesses that are at the growth stage across all industries. It offers investors benefits such as relief on income and capital gains taxes if they invest by purchasing new shares to the value of less than £1 million in total (across all companies) per year and hold the shares for a minimum of three years.

The SEIS (Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme) was launched in 2012 to help startups and early-stage businesses looking for initial funding at the point at which they are starting to trade. SEIS offers greater rewards to investors as the risk they are taking is considered to be higher than those investing under EIS. Benefits include up to 50% of the investment to be claimed back in income tax relief, along with significant reductions in capital gains taxes.

These two schemes did a great deal to encourage Angel investors to add fintechs to their portfolios.

2. R&D Tax Credit

Research and Development (R&D) tax credits reward companies that put money into innovation including startups that are focused on innovative technology. Eligible firms can claim cash payments and/or tax reductions depending on whether they are profit- or loss-making.

Early fintechs take off

Many digital-only firms recovered relatively quickly following the financial crisis, partly due to their ability to use technology to adjust to the new market environment, including a renewed focus on maximizing profitability. That helped bring companies like Google to the attention of some investors that had previously been wary of the industry, particularly following the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s.

Once investors had gotten their heads around digital-only and started looking around them, they could see there were already digital-only financial firms out there. PayPal had shown what could be achieved when it was acquired by eBay for $1.5 billion in 2002, around 77% more than its valuation at IPO.

I think, generally, what attracts VCs, is return on their capital, and then a return on their capital, obviously, is a function of a trend in the world, plus quality of entrepreneurs and teams, who are creating businesses.

Nikolay Storonsky, Founder and CEO of Revolut

After 2008, other fintech firms were starting to demonstrate that success in this field could be replicated, especially given market conditions. The peer-to-peer lending industry was one area of fintech that did particularly well after 2008, as has been discussed above. A number of these firms based in the UK had the advantage of having been founded pre-2008, so they had experience behind them. Once they started to benefit from the banks’ new reluctance to lend, they were even more attractive to investors.

Regulatory support

Fintech was more well-established in the US, meaning investors in the jurisdiction were more aware of the industry, but the regulatory environment remained confused which put some investors off firms in the space. Investors are, understandably, far less likely to hand over money to a firm whose activities may be declared illegal at any point.

In contrast, the regulatory changes outlined above that helped UK fintechs prosper further helped bring firms in the region to investors’ attention. The fact that UK fintechs were not only accepted by the UK regulators, but encouraged, boosted their appeal to both domestic and international investors.

Source: Innovate Finance

What’s likely to happen next?

We need to make sure we continue to preserve all those things. I don't think the capital is going away any time soon, there is plenty of venture funding for great fintech businesses, we have the local talent here.

Rob Moffat, Partner with Balderton Capital

Today (September 2019) we have seen little detrimental impact on the volume of fintech investment caused by the ongoing political instability. Fintech investment in 2019 could even be on track to be more than in 2018, according to Innovate Finance.

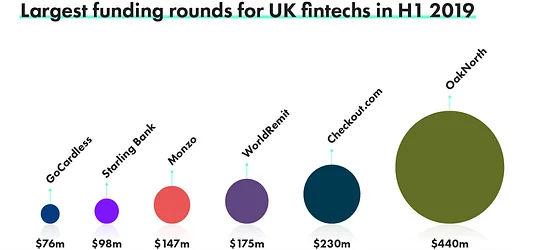

It should be noted, however, that while the volume of capital is increasing, there was a decline in the number of deals seen in H1 2019, continuing a UK fintech investment trend. That decline is potentially worrying, as it suggests that more money is flowing to fewer companies, which could leave earlier-stage or smaller-scale companies struggling to get the funding they need. That could lead entrepreneurs and early-stage startups to base themselves elsewhere – and that’s problematic because a thriving ecosystem needs a constant stream of new entrants to ensure ongoing competition and drive for innovation.

That said, those firms that are attracting later, larger rounds are doing a good job of flying the flag for UK fintech, particularly those which are scaling internationally. That positively reflects on the region, with a history of encouraging the establishment of successful fintechs, which will appeal to investors. It also provides new firms with examples to look up to, follow, and learn from. The UK’s network of experienced founders and to certain extent investors, will further boost its attractiveness to would-be investors.

Source: Innovate Finance

Conclusion

The UK has established itself as a global leader in fintech over the past decade thanks largely to the Government and regulators’ response to the financial crisis. The regulatory changes that were enacted in the UK enabled, and more importantly, encouraged the establishment of fintechs that presented real solutions to customers’ problems.

Importantly, the regulators haven’t taken it easy since, continuing to learn and adapt their approach accordingly. Investors have responded well to that decision, and this combination of factors means that UK fintechs are some of the best positioned in the world to achieve scale and make real change to the financial services industry.

But that’s not the end of the story.

The focus so far has largely been on the banking segment, and fintechs in that space have flourished, making serious waves through the industry as a whole. But attention is increasingly turning to other segments of finance. The insurance industry is ripe for disruption, as are some more complex areas of lending, including mortgages and business capital. The long-term savings and retirement industry is crying out for change, as economic and demographic developments mean more and more people are going to struggle with finances in old age if things continue as they are.

The UK’s fintech hub is a good place for change in all these areas to start as we have a successful model that can be learned from and adapted. The regulators have already started looking at how they can encourage the development of startups in crucial areas. And while Brexit will undoubtedly impact the UK’s economy as a whole, including the fintech industry, this forward-looking approach should help it weather the storm.

Looking internationally, we have already seen countries studying the UK fintech industry in-depth, learning from its development, and implementing adaptations of initiatives used here in their own jurisdictions. The FCA has helped to facilitate this with its international perspective, helping ensure that implementations are appropriate and not just carbon-copies.

We are undoubtedly going to see the establishment of many more fintech focused initiatives across the world until fintech becomes simply finance. The UK has helped lead the way on that journey and others have borrowed and developed what we pioneered along the way, further pushing the fintech story forward. I maintain that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.