How to Enter a Banking Market

Introduction

It’s expensive, time-consuming and heavily regulated. It’s an industry that’s seen little change in hundreds of years and populated by those who are mostly resistant to that change. Furthermore, it remains an industry with an image problem – by and large customers don’t believe financial institutions of any type are working in their favour. So why launch a startup in the banking sector?

Yet in the last 10 years, we have seen a swathe of companies taking on the challenge and launching services that directly compete with those offered by the banks. The most obvious difference between most of these new entrants and the industry incumbents is that they are branchless. They serve customers via apps, websites and in some cases over the phone, but they lack a physical presence on high streets or in shopping centres.

The areas of banking these new entrants are entering varies, but the current (checking) account, in particular, has been reimagined in many different ways. Some providers are targeting underserved demographics such as migrants, others are going after specific niches like frequent overseas travellers and a few are taking on the full banking product stack. They are doing this through the use of new technology-powered features and services that far outstrip those offered by the incumbent institutions in a wide range of areas, from onboarding through personalisation and customer service.

It’s worth noting these new entrants are led by many different types of individuals. Some are ex-bankers frustrated with the speed at which their old organisations were moving, while others are ex-consumers frustrated with their bank’s inability to meet their needs. I spoke to some of these leaders to get a better understanding of the drivers behind their decision to enter the banking market, the different strategies being used to get a foot in the door, and how these banks’ operating models differ not only from the incumbents’ but also from each other.

Why would you do it?

Over the last three to five years the perfect storm of conditions developed in some regions, making it the ideal time to enter a new banking market. In some places, we are now moving past that, particularly when it comes to retail banking solutions, but in others, the time is just right.

Regulatory developments

One of the reasons the UK, in particular, has seen so many new entrants to its banking market is its regulatory environment. One of the country’s major regulators, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), has an unusual mandate to ensure competition in the banking industry for the benefit of consumers – and it takes that mandate seriously.

The FCA, along with the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), has made it easier for those wishing to start a new bank to obtain a banking license by introducing a stepped process. Thanks to the New Bank Start-up Unit, firms can now apply for a restricted license that lets them start working with a small customer base as they tighten up their operations while submitting regular progress reports to the regulators. If they can satisfy the regulators’ requirements, the restrictions will be lifted – a process which should take no longer than 12 months. In proof that the unit has been popular, over 20 license applications were approved between 2016 and the end of 2017.

A number of other regulators have followed suit, with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) announcing a virtual banking license in May 2018, for firms that want to offer banking services through digital channels. It received 29 applications within a couple of months from a combination of startups, incumbents and tech firms. The Australian regulator has also streamlined the application process for new deposit-taking institutions, while one of the US’ numerous regulatory bodies, the OCC, has begun taking applications from fintechs for national banking charters.

The popularity of these initiatives indicates the appetite of firms to enter the market, despite the significant hurdles to success they face. It also shows what a key role regulators play in creating a viable environment for new market entrants.

Customer demand

I won’t spend much time on this, as I’ve covered it extensively before, but customers want products and services that meet their needs and expectations, that get jobs done for them. In banking, as in shopping, entertainment, transport and communication, they want digital, always-on, personalised options – they want intelligent services. But incumbent financial institutions have struggled to deliver and the new guard having spotted that gap in the market, are stepping into the breach.

Technology makes it possible

Technology is one of the key enablers to the creation of new products and services but incumbents either can’t or won’t make the most of it nine times in 10. Cloud processing and storage, open source software and APIs are ever-more accessible. That means minutes-long onboarding processes for a huge range of potential customers are made possible, as are nuanced digital money management tips and the issue of instant digital cards alongside in-app card controls.

Perhaps more importantly, the widespread availability of these technologies means it’s also now possible to stand up an entirely new bank, from core systems to customer interaction channels, at a vastly lower cost than historical solutions involving on-prem software and in-house, proprietary data centres. This reduces the capital required to start a business in the banking industry and opens it up to far more potential new entrants.

Technology is also behind the distribution of new banking products and services to a much broader audience, at a much lower cost, than has been historically possible. Via the internet customers can now find, apply for and activate a product in minutes without needing to leave their homes. This negates the need for branches and creates further cost savings compared to the historical banking model.

How would you do it?

First things first, you need an understanding of the market you are entering. If there are already a number of successful neobanks in a relatively small market, then the operating model you decide on will be different from a region where there is little to no competition, or a market with a huge potential customer base.

With that in mind a number of case studies follow, highlighting how and perhaps more importantly, why, the founders of new market entrants made the decisions they did around technology, licensing and operating models.

Founders’ Stories

Jason Bates, co-founder Monzo and Starling

Jason Bates co-founded UK neobanks Starling and Monzo before starting 11:FS. I got his take on why and how he took on such a challenge.

A fertile regulatory environment, experience, leadership and customer demand are all important drivers behind the decision to enter the banking industry Bates explains. In addition, the technology available to today’s founders also plays a deciding factor.

What do potential customers actually want?

Before entering any market, a firm or founder should identify what gaps a new entrant can fill. Starling’s co-founders started off by trying to get to the bottom of this by asking people what they thought of their bank; unfortunately, most people were pretty apathetic. Then they hit on the idea of asking consumers about their personal finances, and the results were much more enlightening. Answers highlighted how people were finding ways to make products like current and savings accounts, which were to all intents and purposes identical, fit their own needs by doing work around the edges using tools such as spreadsheets.

How do you decide on a model?

Despite the UK having one of the most well-established processes for new bank entrants to acquire a license, it’s still a long process which, back when Starling and Monzo applied, took around 24 months to complete. It also comes with significant capital requirements, and keeping the license once you have it adds overheads to the business. Also, a license to offer a current account product is not required, so why would you bother?

Bates explained that the benefits of being a fully licensed bank – the ability to earn net interest margin, the customer trust and the ability to hold and lend deposits – outweighed the costs as far as Monzo was concerned. That said, the founding team also decided to go for best of breed. They launched a prepaid card product to customers while awaiting a full license; a period which allowed them to build and iterate on Monzo’s app, and to create the intelligent services the firm provides. To Monzo’s founders, that was lowering the risk they were taking by finding out if their product was viable and faster, and if it was getting some early traction in terms of viral growth.

Other entrants have decided not to publicly launch until they are fully licensed and their product is several stages beyond a Minimum Viable Product (MVP). Bates believes the biggest factors at play when a firm is making a decision about when to launch is the type of company it wants to be, along with its appetite for risk.

The market changes over time

The iterative approach worked for Monzo which now has over one million customers, but would it also work for firms wanting to enter the UK banking market today, a sector that now has more than 30 new entrants offering banking products?

The main deciding factor remains, how confident are you that customers will want your product? Arguably, in a more mature market, it’s better to just get the thing out there – other people have already done the first steps towards viability testing so you might as well skip them.

In the current UK market, it would make more sense to look around at the wider financial services ecosystem, where everything from mortgages to credit cards is starting to be disrupted and look for a gap there, rather than trying yet another take on the current account.

Goldman Sachs

Omer Ismail heads up Goldman Sachs’ consumer business in the US, which operates under the Marcus and Clarity Money brands. Goldman Sachs has not only entered the retail banking market in the last two years, it’s done so in two different geographies.

Why enter a new banking market?

Goldman Sachs became a bank holding company in 2008, which meant it was able to start retail banking operations where previously it was an independent investment bank. However, it didn’t actually begin exploring opportunities in the consumer banking space until 2014. Having internally established that there was a gap in the market for a digital-only offering that helped repair customers’ relationships with their money, and in so doing gave them more control over their financial lives, they got to work.

Goldman Sachs had a significant advantage over its incumbent peers that were also looking to establish digital-only retail banking offerings – it lacked legacy technology and business models so it could start from a truly greenfield position.

Where do you start?

Goldman Sachs entered the retail banking market with a personal loan product in 2016, followed swiftly by a high-interest savings account, both under the Marcus brand. The products are only available via the website, no app yet exists but the strategy of launching two complementary but very simple products, with market leading rates, has been hugely effective. By September 2018, the Marcus brand had accumulated $20 million in deposits and issued $3 million in loans.

Phase two of the product development came in 2018, when Goldman acquired a personal financial management (PFM) app called Clarity Money. The aim is to eventually offer a platform consumers can use to manage their entire financial lives in one place.

How and when do you expand?

After Marcus’ success in the US, Goldman decided to bring it to the UK – another market poorly served when it comes to interest-generating deposit accounts. As with its US product, the UK savings account is incredibly simple with only the bare minimum of features (deposit, withdraw, print statements and little more) and that extends to the customer onboarding journey. Within three months, it had accumulated £5 million in customer deposits in the country.

In the UK, Marcus requires customers to link it to one UK current account, which becomes the only means of depositing and withdrawing money from the savings account. That promotes habitual saving as it makes moving money between the two quick and easy. Ensuring external transfers can only go to one location also helps to reduce fraud as it becomes nigh on impossible for fraudsters to extract money from the account, even if they have the customer’s full details.

Is success guaranteed?

Marcus’ success in the US was perhaps more probable than in the UK, given it was on home territory and the country’s neobanks have gained lower penetration. The fact that it quickly became successful in the UK shows that there are still gaps in the banking market for those willing to specialise – which adds weight to Jason’s hypothesis.

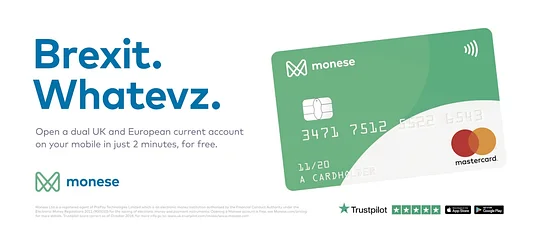

Monese

Norris Koppel is the CEO and Founder of Monese, which provides full UK current accounts to customers in the country and across Europe. It targets people who “live their financial lives in multiple countries”.

Why aim to serve a more niche demographic?

Marcus and Monzo are squarely mass-market propositions; beyond requiring customers to be reasonably tech-savvy, they appeal to a wide range of demographics. Monese, on the other hand, is entirely focused on a particular group of people. Koppel explained that Monese’s foundation is similar to many other startups in that it was the result of a situation that caused him significant personal frustration. His own struggle to get a bank account after moving to the UK from Estonia inspired him to create an account that could be opened in a quick and easy manner by others in similar situations. And by doing so, he and his team would be solving a serious pain point for a large number of potential customers.

Monese’s customers, over a million of them, also use its services in a different way to the majority of many of the other new banking entrants – they utilise it as their primary account. This is partially attributed to the additional services Monese offers, such as providing support in numerous languages, and the make-up of its particular user base is also a contributing factor.

Why not get a banking license?

Koppel’s decision not to apply for a banking license was down to his ambition to take the company global from day one. A UK banking license would only have allowed Monese to operate in that region and obtaining further banking licenses in Europe would have required resources the firm was unlikely to have access to for the foreseeable future. So, Koppel and his team looked for a lighter regulatory alternative that would facilitate the easiest possible expansion. The result was Monese’s acquisition of an e-money license from the UK regulator, under which they can operate across much of Europe. Now they are looking at how to expand further afield, a strategy with numerous strands.

How do you ensure your technology will let you scale quickly?

You own the key components and partners for others, according to Koppel. In Monese’s case, it decided to own the system that controls the flow of funds from end-to-end, which forms the core of its product. Monese also developed proprietary technology for facilitating identity checks so that, while additional customer due diligence data is sourced from third parties, it can handle applications from consumers without UK addresses or ID and make approval decisions in-house in a matter of minutes.

In other areas such as card issuance and overseas transfers, it made more sense to partner. However, relying on partners can have drawbacks in that your services are subject to their technology’s stability.

How do you decide on a business model?

Unlike its peers with full licenses, Monese can’t make money from holding customer deposits and issuing loans. Instead, it partners with other providers of those services and takes a margin when customers use them. It also offers a tiered pricing structure, which ranges from a free account through to one that costs £15 a month. This means Monese earns a little less revenue per customer than the likes of Monzo and Starling, but it has access to a much larger number of potential customers thanks to its pan-European scale.

What does the future look like?

Monese has had more cause than many to plan strategically for the current UK political environment, given its customer base and pan-European business model. It has already acquired licenses in multiple jurisdictions to ensure continuity of service and has offices in Tallinn, Lisbon and Berlin. Its approach to the situation is reflected in recent advertising campaigns, which include repurposing the “Brexit Bus” and crashing a “Brexit meteorite” outside of a train station in London – no matter what happens, Monese says it will be there for you. Additionally, Monese’s main strategic focus, expanding outside of Europe, is unlikely to be affected by a negative Brexit outcome so it is well positioned to maintain its current growth trajectory.

Mettle

11:FS has entered several new banking markets, one of which is a new bank account targeting SMEs for NatWest called Mettle. I spoke to Ewan Silver, CTO of 11:FS and Mettle to find out why and how we did it.

Why did NatWest want to re-enter a market they already dominate?

The bank has a significant share of the UK SME account market, so its decision to launch a new account in the same market is an interesting one but it wasn’t the bank’s original plan, according to Silver. 11:FS was brought in to run our 12-week program, which establishes what the customer’s problem is and if there’s an effective way to solve it. In this case, we were asked to look at the impact of Open Banking on the SME current account market and what we discovered was that by and large SME owners wanted a forward-looking account. That means an account that tells them what they should do next financially, be that chase an invoice or how much to file in their tax return, as well as what they have already done.

How does a big bank do things differently?

Rather than trying to build an entirely new product within the existing organisation, a separate, modular architecture was built for Mettle enabling it to operate separately from its parent. This approach meant Mettle could be built using a similar model to challenger bank peer Monzo, with a minimum viable product (MVP) being created in just six weeks. Its core capability is a prepaid card powered by a third party which gives users a UK sort code, account number and access to faster payments. And rather than going through the process of getting its own banking license, Mettle operates under the e-money license of that third party which further sped up time to launch.

What’s next for Mettle?

For now, Mettle only serves freelancers and the team’s focus is on customer acquisition and working with consumers to explore what features will most increase Mettle’s utility for them. In future, the range of services offered will likely expand to serve a wider variety of demographics, such as larger SMEs and those in industries with more complex financial requirements e.g. manufacturing and hospitality. These groups have larger volumes of cash flow and often need access to a wider range of systems.

What are the biggest hurdles big banks face in taking this approach?

Given his experience working with big organisations to build new financial products and services using innovative working practices, I asked Silver what he thought the biggest hurdles were to success in this area. His answer was not the often suggested legacy technology, but rather legacy processes, and in particular, governance. Within financial institutions, current product development processes are too linear, with work passed from one team to the next only when the former has “finished” with it. The two major problems with this way of working are that: it takes a long time and therefore a lot of resources; and flaws within the product, such as a compliance failure or poor customer fit are baked-in early on and only discovered when the relevant team gets their hands on it.

What’s the solution?

Silver believes that building combined teams including people from engineering, design, compliance etc to work on a product end-to-end leads to a faster time to market, as well as better products overall. This is the way that many of the neobanks work and thus far, it looks to be successful. That said, as yet all the UK neobanks have fewer customers, and far fewer employees than the incumbents. It remains to be seen whether their ways of working will continue to be effective as they scale.

Other strategies of note

There are not as many strategies for entering a new banking market as there are new entrants, but there are a few others not yet mentioned that I’d like to call out.

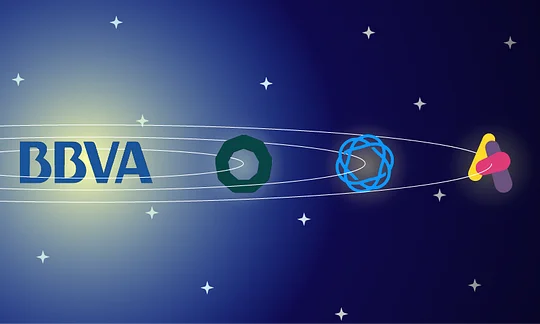

BBVA’s multi-pronged strategy

BBVA has employed a multi-faceted strategy as it seeks to enter a range of new banking markets, while simultaneously digitalising its core bank. It bought Holvi, a Finnish challenger, which provides accounts to entrepreneurs and sole traders, but the firm still operates independently. In contrast, the bank’s US arm, BBVA Compass, bought challenger retail brand Simple Bank and transitioned customers onto its own platform. BBVA also holds a 40% stake in UK challenger Atom Bank which offers savings and mortgages, providing the Spanish bank with a third strategic market entry. This strategy of investing and purchasing to target different geographies and demographics is a spreading of bets, of which at least one will likely prove successful.

Infrastructure players

The main focus of this report has been on the launch of new customer-facing products, whether they be corporate or retail; however, it would be remiss not to mention the firms that have entered new banking markets as innovative suppliers to the banking industry.

solarisBank

The German firm, founded in 2016, offers Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS), allowing third parties to build financial services using its modular platform and under its banking license. Customers can pick and choose which financial services they want to offer, for example, bank accounts, cards and consumer lending can be incorporated into consumers’ own products via API. It enables the unbundling of banking and payments products, allowing users to focus on one core product or service and ensuring that is done well. Additionally, it offers services such as payment processing, KYC and AML compliant digital ID checking and a Blockchain Factory for companies working in the cryptocurrency space. Not only is it arguably a new entrant to the German banking industry given it holds a banking license, but it is also facilitating the entry of other startups to the same market.

11:FS Foundry

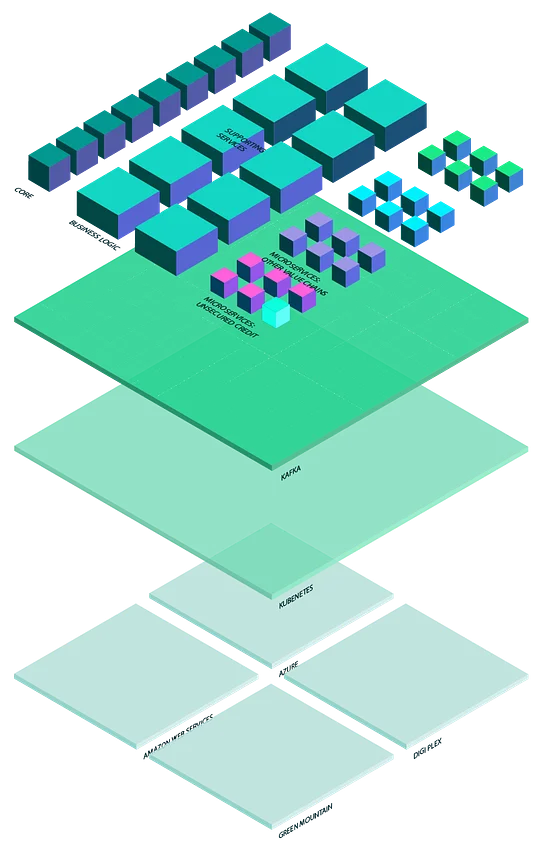

11:FS Foundry is a modular core banking platform designed to permit customers to launch digitally native propositions at speed, low cost and with no compromise between agility and scalability. Because of its modular nature, Foundry allows customers to pick and choose what they need rather than expecting them to buy a monolithic system whether they need or want it all or not. That reduces time to launch and ensures firms can adapt offerings quickly and easily in tune with their customers’ demand. It also means providers can rethink how they develop and launch core products, enabling them to move in a step-by-step fashion and learning from each stage, rather than taking years to do a complete overhaul, especially as Foundry can integrate with existing third party and proprietary systems. Foundry is one of several new players in the core banking space but there’s room for more than one to succeed. The fact that it can as easily work alongside any other system as it can replace them, that it works at scale and that it offers the genuine possibility of reducing risk in a replatforming or new product launch should help it stand out from the crowd.

Starling

Originally a retail bank, Starling has moved into other banking silos with the launch of its business account, its Payment Services and its BaaS product. The former means that third parties can connect to UK and European payment systems via Starling, speeding up the time taken to access these rails. The latter, similarly to solarisBank, means other fintechs can use Starling’s APIs to open customer accounts and provide them with cards among other services, under Starling’s license. This suite of products means the bank is entering new markets both vertically and horizontally – it’s offering customer-facing products and the infrastructure that supports these products at the same time.

ClearBank

ClearBank’s customers are other financial services firms. Launched in 2017, it provides clearing and settlement services as well as core banking software to regulated financial firms including banks and fintechs. Its cloud-based platform is brand new and the bank says that enables it to serve smaller financial players more cheaply and efficiently than its incumbent peers. Additionally, unlike the UK’s other clearing banks, it doesn’t offer any retail or business banking services, choosing to focus on being an infrastructure player instead. ClearBank’s strategy is one of the more unusual ways of entering a new banking market and required significant upfront outlay in terms of time and money. For now, it faces little in the way of competition from other new entrants which should give it a head start in capturing its target market and while customer-facing brands attract the most attention, we shouldn’t ignore the so-called back-end players which are modernising banking behind the scenes.

How to Break into Banking

The above case studies and examples show a number of different strategies that have already been used to enter new banking markets and there are valuable takeaways from each of them. However, firms thinking of joining their ranks should also bear in mind that the global financial services market has an ever-growing number of new entrants and they should not look to create a carbon copy of any existing product, service or model if they wish to succeed.

-

Find your beachhead

Decide which product or service will lead your go to market strategy. In some cases, that product or service might be highly complex and take significant time and resources to bring to market, such as in ClearBank’s case, in others, it might take as little time as weeks to launch an MVP. The most important thing is to ensure it focuses on one key area and you can find out what actually works in that market before you attempt to broaden your offering.

-

Create a community

Some of the most successful new market entrants, most notably Monzo, have built communities months ahead of launching. That’s translated to free marketing and an almost guaranteed group of early adopters, many of whom are willing to use a product that is still being iterated upon while providing valuable feedback. Later entrants have followed suit; however, this strategy is no guaranteed means of success and requires intensive planning to get off the ground effectively.

-

Build a brand

This is linked to both previous points but should not be overlooked. Brand identity is still important, particularly if you are entering a crowded market. As a result, any firms attempting to enter new markets should have a full strategy in place that outlines what values they want to embody and how they want to be perceived by their chosen market.

-

Rethink your processes

Key for any existing firm seeking to break into a new area is to ensure your organisation is prepared to learn about and adopt new ways of working and even more importantly, to explore new business models. Trying to build an innovative product or service is hard when you are held back by years and years of historical processes and linear development patterns. One of the very first steps organisations should take is to explore HOW they are going to build something new, in turn that should help ensure the maximum chance of success for the WHAT they develop.