Best In Class Digital Money Managers

Introduction

People are managing their money using digital tools and services. As many as 70% of UK consumers now use a phone app to keep track of their money, according to Yolt. However, there are huge differences in the quality and value of what they are using, and the sheer volume and variety of offerings in this area is ever increasing. I’m going to help make sense of this picture for you, and outline what’s required for a best-in-class digital money manager.

People are using many methods to help them manage their finances – tools and apps from their banks, third-party apps and services, and paper-based statements and communications. This situation is being driven by the growing popularity of having multiple financial products from different providers, global economic conditions leading people to pay more attention to their finances and the fact it’s now commonplace to use digital means for interacting with providers e.g. online banking.

For years these products and services have been known as Personal Finance Management (PFM) tools. They are designed to make it easier for consumers to track, stay on top of, and generally manage their finances. However, when you ask people what the term PFM means to them, you will get a huge variety of answers – it could mean a spreadsheet, a specialist app, or even an analogue process involving a notebook, paper receipts and statements and a pen. This suggests that the term isn’t useful for the purposes of this report, so, instead, I’m going to call the area under discussion digital money management.

If executed properly, digital money management tools and products can be intelligent services i.e. real-time, contextual and problem solving but clearly that’s harder said than done. It requires high levels of customer engagement and gathering significant volumes of data in order to provide suggestions and nudges – or “actionable insights”. For example, there’s no point suggesting someone move £100 from a spending account to a savings account this month when their quarterly gas bill is coming up, which is paid out of their joint account and they won’t have enough money to cover both.

The data isn’t the currency, the insights are

Jossie Ellis, Money Dashboard

In this report you’ll find sections on why customers are turning to digital money management, an overview of the types of company operating in this space and the sorts of solutions they offer, a selection of case studies with interactive highlights and my recommendations for how to create a best-in-class digital money management product.

Why are people using them?

Expectations have changed

The internet is now accessible by huge sections of the global population. That’s spurred the growth of internet businesses which have become permanent fixtures in people’s everyday lives. From Google, and Amazon, to Alibaba and Tencent, Rakuten and Paytm, these firms have changed our expectations around how businesses should interact with us – and us with them.

Access to services and platforms is expected 24/7, while if we don’t receive real-time notifications about status changes, accounts or orders we’re likely to complain, often publicly via social media. These expectations have been set by the internet giants which realised the need to prioritise frequent, interactive engagement with their customers in lieu of building in-person relationships if they wanted to ensure retention.

It’s also now considered a requirement to make business to customer (B2C) interactions as simple as possible. The fewer steps to a customer getting what they want is typically considered the better, whether that’s via a digital interface or not. The tech giants perfected user journeys of this kind in order to remove friction and ensure the customer achieved their desired outcome, before they were distracted by something else happening online.

The permeation of this type of company into everyday life, from shopping to entertainment, education and employment, finance and health, has exacerbated the impact had on expectations to the point where people are now outraged at any company that doesn’t meet them. And that includes financial service providers.

Digitisation

The ability of Google et al. to influence expectations to such an extent has only been made possible by advances in technology, particularly the widespread adoption of smartphones. In turn, this opened the floodgates for technology to play a part in every aspect of our lives. As smartphones become ubiquitous this will only increase.

It’s now possible for us to check the news, shop, find directions, communicate and much more besides from the devices in our pockets or bags. And, as mentioned above, we expect companies to provide ways for us to do that. For the most part, they have succeeded, whether that’s the legacy players in their industries or new entrants, much of the time we can get what we want purely via our smartphones.

That can only happen thanks to instant messaging, digital cameras, biometric security, tokenisation, digital signatures, GPS and many more technologies and services. These technologies are everywhere, and – increasingly – so is people’s ability and more importantly, willingness, to use them.

Financial firms are no exception to this trend, they are working hard and fast to digitise their products and services. Although it must be said this has been with varied success – few have yet understood the difference between digitisation and digitalisation, an area explored in one of our recent blogs.

People are less financially stable

Since 2008 people’s financial stability has been eroded by an increasing number of factors. The crash and the subsequent fallout resulted in vast numbers of job losses, home repossessions, high inflation and a lack of available credit across the board. One outcome of this changed financial outlook in much of the world was an increased preoccupation by individuals with their day to day financial situation.

Unemployment fuelled the explosion of the gig economy as people decided some work was better than none, but this added complexity to many people’s finances. Instead of a monthly payment of a set amount, workers in this section of the economy now have to budget on a much more frequent basis – in some cases daily. Add to that the soaring cost of living in many cities around the world and all of a sudden people had plenty of reasons to want to keep a closer eye on their money.

Who offers digital money management?

There are endless numbers of companies claiming to help people with their finances. From startups to established financial services firms and non-profit organisations, they are all offering ways to help individuals keep on top of their money.

Startups

Typically startups offer features such as rounding up transactions from a linked payment card and automatically moving the extra funds into a savings or investment account. Others aggregate data from multiple financial accounts to give users a holistic overview of their finances.

These firms use a variety of business models:

- Acting as suppliers to financial institutions, as in the case of Moven,

- Using a freemium model like Plum,

- Or a pricing scale starting at a very low price e.g. Acorns, which charges only $1 a month for its basic offering.

These models seem to be working for these examples, but there’s also been considerable consolidation in this market. Level Money was bought by Capital One which went on to shutter the service, Zenbanx was bought by SoFi and then discontinued, and BillGuard, which was bought by loan provider Prosper, rebranded as Prosper Daily and then shut down last year.

The closures of startups, even when acquired by larger players, suggests that while these tools may be amassing customers, many are struggling to operate sustainably. The exception to this trend is Mint which has been around over ten years. It was bought by Intuit in 2009 and continues to be a key component of their product suite.

Banks

Banks, meanwhile, are starting to grasp the popularity of these tools and integrate them into their digital channels. The challenger banks, in particular, have included money management tools, built in-house, from the beginning as part of their customer acquisition strategies. The likes of Monzo and Starling in the UK and Chime and Simple in the US set out to change the reputation of the finance industry by showing customers that banks could work in their customers’ best interests. This group believes that helping people better understand their money is key to ensuring brand loyalty in an increasingly crowded banking market, and consequently have delivered high-quality money management offerings integrated with their core offerings.

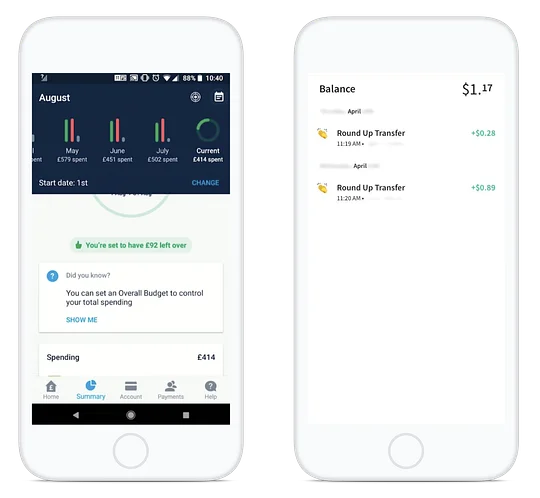

Monzo’s Spending Summary Page and Chime’s Round-Up Feature

Larger, older banks have also toyed with money management offerings. Lloyds launched its Money Manager product back in 2011. It features automatic categorisation of transactions, graphic representations of spending and savings goals, but falls down in a number of areas. It’s an opt-in service, which is relatively hard to find being located menu at the bottom of a sidebar on the online banking landing page. It also assumes Lloyds is the user’s only bank and struggles to categorise transactions accurately with a large number ending up in the “other” section.

These flaws are common to bank-built digital money management tools, and are typically the result of conflicting stakeholders within the bank and difficulty in connecting different systems and data sources. The result is that they end up as peripheral services rather than embedded into the customer’s account and with limited utility, causing low adoption rates.

Other incumbent banks are using third party suppliers to power digital money management services. Companies including Canada’s Personetics, the US’ Moven, and UK-based Meniga all offer white labelled solutions to financial institutions which can save time and money when it comes to implementation, but does leave their clients struggling to ensure differentiation. Another problem with using a white-labelled solution is that the bank doesn’t have complete control over the service delivered which leaves them vulnerable to down time and other issues on the supplier’s end.

Who’s doing it well?

Startups

The firm I believe has come furthest in digital money management in the last few years is Yolt. It combines the best new technology has to offer with a customer-centric approach that helps it to stand out in a busy market. Yolt is a venture of Dutch bank ING N.V. but operates as a startup in the UK. Its app-based service is one of the new guard of account aggregators aiming to be the only provider a customer ever need interact with. It allows users to see multiple financial accounts in one place and auto-categorises transactions from all accounts to give the user an overview of their total spending on areas such as transport and utilities. Users can also set and track budgets for particular spending types, such as eating out, and access services from third party providers including international money transfer and home insurance.

One of Yolt’s primary aims is to make managing finances as easy as possible for customers. To facilitate that it connects to the UK’s nine major banks using APIs, as well as new banks Monzo and Starling, and has worked with each of these providers individually to make the user journey as quick and simple as possible. That’s moving away from processes typically used by aggregators which required users to hand over user IDs and passwords through detailed forms. That allows aggregation services to gather, or “screen scrape”, information from different accounts to provide a single overview.

Yolt’s revenue model is currently based on receiving commission when a customer chooses a third party through Yolt, similar to many other money management startups. However, unlike most of its peers, Yolt has the brand and financial advantages of a large bank backing it while it builds on this model, meaning it can leverage the strength and stability of a corporate along with the innovativeness and agility of a start-up. In future, Yolt plans to add a wider range of services based on what its users are most interested in, including payments, build out its partner platform and expand into more European countries.

Money Dashboard was one of the first players in the digital money management space, having been founded in 2010. Originally an online service allowing customers to view all their accounts in one place, it evolved over time into an app which offers a range of additional services like budget-setting. Money Dashboard initially used screen scraping methods to enable customers to access their data but was an early supporter of open banking and is moving towards using APIs wherever possible.

Over time, Money Dashboard has had to adapt to the changes in consumer behaviour that have occurred over the last eight years. People hold more accounts now, but that means greater numbers of transactions to keep track of across a wider range of institutions. Consumers also increasingly feel, thanks partly to broader societal changes and partly to education campaigns from charities and regulators, the need and want to be more financially prudent. They want to raise their own understanding of what their finances should look like if they want to achieve particular goals. All of this has raised a greater desire to actively manage money, while technology has made it ever more accessible, helping to explain why Money Dashboard continues to attract new customers.

Unlike many other providers in this space, Money Dashboard’s primary business model is not based on cross-selling products from third parties. Instead, it centres on gaining insights from its customers’ anonymised data which are then sold to groups interested in consumer research. In future, the company will look at pushing further into the B2B space.

Other providers in this space

Aside from aggregation, the other area we have seen significant movement in is helping people move money to where it better works for them in a simpler and more user friendly way than previously.

Moneybox connects to a user’s payment card and rounds up each transaction to the nearest whole pound, It then moves the “roundup” to an investment account with a risk setting chosen by the user. The aim is to encourage more consumers to invest their money by keeping amounts small and automating both the contributions to the portfolio and its ongoing management. For now Moneybox’s functionality remains somewhat limited but it will likely build this out in future in order to accelerate a move towards sustainability.

US-brand Acorns has a similar proposition with added features and functionality, including the option to multiply each round up by two, three or ten. It also offers users rewards when they shop at certain merchants in the form of money added to their portfolio, rather than the more traditional cashback. Recently, Acorns launched a payment card which enables the brand to offer customers a wider range of financial services along with advice on areas like retirement strategies. Overall it’s a much more holistic proposition than Moneybox, aiming to become the customer’s primary financial account which gives it the benefit of more volumes of customer data and greater opportunities for new revenue streams.

Cleo, which is available in both the US and the UK, takes a different approach by operating through SMS, Facebook Messenger or Amazon Alexa. Once a user has connected their accounts they can interact with AI-driven Cleo to find out what they have spent their money on, how well they are sticking to a budget and whether they can afford a certain purchase at that moment. Cleo will also recommend users move money into a savings wallet at least once a week based on how much disposable income they have at that point, if they agree, Cleo moves the money for them. Users can also instruct Cleo to move a certain amount into the savings wallet at any time. While the proposition is interesting and well executed, the firm’s business model has yet to prove itself and until it does, it remains in the same camp as many other digital money management offerings – a feature rather than a stand-alone product.

Banks

The first bank to successfully incorporate useful money management tools into its digital channels was an American challenger which made the decision to include such services from its inception.

Simple bank, which was acquired by BBVA in 2014, was conceived back in 2009 as the most “simple” a bank could be. It would hold customers’ money for them safely, facilitate electronic payment and transfers, and enable customers to lend money to others in exchange for interest or to borrow at a risk adjusted rate. The most revolutionary tenet of the bank however was the fact it would give users complete and open access to their data. The data would then be used by the bank to help users make financial decisions, such as which was the most appropriate loan for them.

Simple’s founders decided from the start that they would include money management tools having had poor experiences with the other tools available. Having realised that screen scraping resulted in tools that were neither useful nor user-friendly they then focused on direct access to data.

Shamir and Josh’s goal was to build tools into customer’s core finances, automate that management and make it as easy as possible for users. They understood that most people don’t want to manually manage their finances, finding it time consuming and annoying. This decision to include money management tools as part of Simple’s core offering is key to the bank’s ongoing success.

Josh and Shamir had a great vision for the variety of tools they wanted to include in the first version of Simple but, with some help, came to understand that starting with a few excellently executed features, was a much better plan. There’s no point delivering a huge number of features, none of which work, because that will alienate users.

Other banks of note

Chime is one of the front-runners when it comes to money management-centric neobanks in the US. As of September 2018 it had opened 1.7 million accounts for customers with features including automatic savings and cash round-ups. Customers can choose to get 10% of their paycheck automatically moved into their savings account as well as get paid via direct deposit. The Chime app enables customers to receive instant notifications when funds enter or exit their account, as well as daily balance alerts. In terms of what’s next for the firm, Chime recently acquired Pinch, a startup that aims to help people improve their credit scores. That suggests that we’ll see new credit-focused products coming from Chime soon. Customers obviously like what they do as around 50% of customer acquisition comes from referrals.

UK challenger bank Monzo has over one million customers, to whom it offers a range of digital money management tools to all customers. It will roundup transactions and move the roundup into a separate savings “pot” if requested, allow customers to set budgets to avoid overspending, show users how likely they are to run out of money that month, allow them to view spending by category and send notifications if they are running low on funds. It also takes into account, and shows, upcoming bills and “committed spending” providing a more accurate picture of the customer’s financial position. Monzo’s money management tools are among the most advanced I’ve seen in terms of variety and accuracy, while remaining easy to use and simple to understand. Importantly they are also front and centre of the bank’s offering which means they will only become more useful to customers over time while facilitating high levels of engagement.

HSBC was the first bank in the UK to take advantage of the country’s open banking rules by launching an app called Connected Money. For now, use is restricted to HSBC UK customers with online banking and an up-to-date iPhone. This group can add and view accounts from 31 different brands in one place, see their total spending in different categories across their accounts and access analytics and insights into their spending. Its limited availability means it’s too early to say how useful to end users Connected Money will be, but HSBC will have to move fast to iron out any bugs and roll out additional features if they want to compete effectively with startups also in this space.

What's next?

Integration

Aggregation services are starting to integrate a wider variety of products into their offerings, enabling them to give customers a better understanding of the overall state of their financial positions. Realistically this is the only direction for such tools because until users can see all the financial products they want in one place, including loans, investments, pensions, mortgages etc., they won’t be useful to most.

The same is true of automated savings and investment tools – connecting to just one account is not enough to have an accurate idea of someone’s overall finances. In fact, recommending someone a) invest and b) how much, without having the full picture, is somewhat irresponsible. These services need to find a way to access a user’s holistic financial situation to provide accurate recommendations and useful products.

Banks offering digital money management tools also need to let customers interact with products held by other providers if they want customers to fully and regularly engage with their offerings. Practically no-one has all their needs met by one provider when it comes to financial services and banks need to accept that this is the future. Open Banking will go some way to facilitating these integrations, but banks need to ensure interoperability is central to their strategy.

More useful tools

Integration with other providers is just one way the more enlightened firms are moving towards creating intelligent services. The provision of increasingly actionable insights such as in-app utility provider switching when it will save customers money on their bills and advance warning of upcoming bill payments are also steps in this direction. But there’s still some way to go.

As providers persuade customers to connect all their accounts and start engaging regularly, insights can be ever more accurate and personalised, and the choice of useful actions provided to the user will increase. This is the end goal all money management services should be aiming for.

Consolidation

Consolidation has started in this area as business models have failed to evolve, services have been poorly thought out, tested, or executed and firms have failed to persuade customers of the value of their offerings. Aside from Mint’s acquisition by Intuit, there has been little successful integration of acquired money management services into broader propositions.

We will certainly see more consolidation globally in the digital money management space as many startups realise what they have is a feature rather than a stand-alone product and end up being acquired or closing down completely. Other startups will overreach themselves and end up losing sight of what their customers actually need. And banks will realise that success in this area is not achieved by having the most resources, forcing them to wind down and revamp unused products probably by using third party features and services.

What it takes

- Ease of use. Do not underestimate how quickly customers will walk away from a service that is overly complicated to use, especially when it comes to digital money management. Use the fewest steps possible for signing up, logging in, integrations, setting up budgets and notifications and finding features. Keep designs clean and uncluttered and use widely understood language rather than specific financial terms. If need be, provide a glossary.

- Integration. Let users access as many of their financial products as possible. Where it’s not possible, work with third parties to offer alternatives. No digital money management tool is useful if it contains limited data.

- Iterations. Listen to your customers, make changes based on their feedback, and don’t be afraid to make changes. That’s especially true if you are categorising and labelling, money managers are no use whatsoever if users don’t feel they are providing an accurate picture of their finances. Do be warned that when it comes to money management tools specifically, some people will always flinch at change but if a new feature, layout or process will genuinely improve the experience for majority of customers then do it.

- Make insights actionable. Many of the earliest tools in this space failed because they provided analysis that was too deep and complex for most people to understand, or just raw data that didn’t enable users to easily take action off the back of it. To foster engagement and loyalty, all insight needs to come with an accompanying action, suggestion or comment.

- Aim for intelligent services. The end goal should always be to make customers’ lives easier. It should never be about providing vast volumes of analysis and graphs, or offering many features as possible without any guidance as to what’s right for each individual. It should be about helping customers get out of debt, buy a holiday or a house, or simply save them time.