Why big banks are doing challengers: Brand Permission and why it matters

The whydunit is an increasingly popular narrative. More often than not the motives behind a decision are more interesting than the decision itself, so I’ve taken a look at the motives behind big banks and their fixation with challengers.

Creating a challenger product isn’t easy. Incumbents have spent years, centuries even, cultivating a brand that’s imposing and demands respect. How can they shift from being a serious authority figure in your life to someone who talks to customers as equals?

Brand permission is an interesting concept. It sounds like the sort of Don Draper, Mad Men, ad-agency bullshit that makes your skin crawl. Yet when you dig into the psychology of it, it makes more sense than you'd probably want to admit.

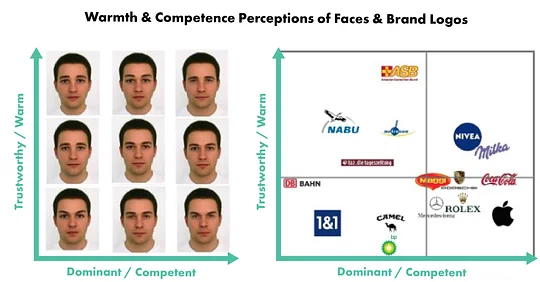

Humans use the same psychological framework to process and judge brand logos as they do faces of the people around them.

That means we humans, with all of our quirks and flaws, are making emotive and judgemental decisions about a brand, with all of the prejudices we might apply for a human. If we see white hair and wrinkled skin, we associate that with old age. If we see athletic builds, we associate that with health.

How we evaluate brands (and faces)

To simplify things, Anne Lange, Professor of Experimental Industrial Psychology at the University of Lueneburg, developed two axes in an experiment:

- Trustworthy / warm: Respondents were asked a series of questions to understand if a face (or brand) would act in your best interests, did they have good intentions, were they trustworthy or caring?

- Dominant / competent: Respondents were asked a series of questions to understand the ability, skill or how dominant a face was

To summarise these findings they were then able to plot the faces (and brands) on the axes:

Image credit: fidelum.com

The twist is, human appearances and faces change and adapt. The athlete may not always have looked that way. The old person was once young. A person can smile, raise an eyebrow or scowl. Brand's 'faces' (logos) rarely change and when they do, it’s rarely radical.

What is Brand Permission?

In 1999 Seth Godin wrote a book called Permission Marketing. Godin observed that successful brands were ones that obtained the consumer's consent to market to them (and he didn’t mean an opt-in tick box, but emotive, genuine consent). He then noted three core elements to permission marketing:

- Anticipated: people will anticipate the service/product information from the company.

- Personal: the marketing information explicitly relates to the customer.

- Relevant: the marketing information is something that the consumer is interested in.

If you invert these you also get, not anticipated, not personal and not relevant. The first point about not anticipated is key to understanding your own brand permission.

Understanding your own brand permission

In banking particularly there’s a real push for 'Innovation'. Without care, this risks being perceived by customers as similar to their grandparents at a rave, or a politician naming the latest breakthrough artist as their favourite in interviews.

In many ways, brands are quite static and do best when playing to their strengths. You wouldn’t want the banker to help you choose an outfit to wear. You wouldn’t expect your bank, which has spent the last 3 decades being aloof and corporate, to suddenly be your best friend and on the cutting edge.

While older brands may find themselves in the 'dominant/competent category', that’s not necessarily a bad place to be. However. when doing an innovative product launch brands must consider whether their customers feel like this should be coming from them, or should it come from a new brand?

Telco O2 (Telefonica) understood this well when in 2009 they launched the Giffgaff brand in the UK. Teenagers mostly bought cheaper prepaid SIMs, and no matter what pricing O2 offered, teenagers were not drawn to those offers. By launching Giffgaff with some unique product features (e.g. being one of the first to offer 3G data on prepaid) and a new brand, they now had permission to market in a completely new way, with a new tone of voice and a new product offering.

What this means for brands

At 11:FS we often talk about the war for customers, and place this on the Banking Battlefield. The key is understanding where do you want to start on the banking landscape with regard to:

- Your existing tech capability

- Your existing culture

- Your existing brand permission

Each position on the banking battlefield has different strengths and weaknesses. But there are opportunities for incumbents, challenger banks and big technology companies to leverage their existing brand permissio, or to start somewhere else on the battlefield as a hedge to the main business. We are increasingly seeing the latter from large banks with brands like Marcus by Goldman Sachs, Yolt by ING and of course, Mettle by Natwest.

A word on big techs

The threat looming on the horizon for a number of years has been the big techs: Google, Apple, Amazon and Facebook in the West, and in Asia, of course, the Alibaba, Tencent and Grab super app players.

All of these organisations have made a play in finance. Most notably, Apple recently launched their own credit card and as CEO of 11:FS David Brear pointed out, they’re able to leverage their platform and position to win a greater share of the customer relationship and more of the value that comes with it.

Amazon Pay is slowly growing, as is Google Pay, while WeChat and Alibaba are already fully fledged financial services businesses. The one thing you see in common where big techs succeed is they play to their platforms’ strengths. They understand the brand permission they have with their customers and build on it.

That doesn’t mean that the big techs are unstoppable, infallible or incapable of being opposed. I’d look at Facebook as an example where this platform-based approach hasn’t worked as well. The social media giant holds a number of payments licences, but as yet haven’t made that real breakthrough in payments like Apple or Alipay have.

What happens next?

At 11:FS we’ve helped a number of incumbents, big techs and fintechs identify the strategy and execute on that strategy depending on their position on the banking battlefield. Your strategy to acquire (or keep) customers will depend on where you start from and where you want to get to. It requires a deep understanding of your brand permission and if your existing brand has an unfair advantage that you can build on.

Where are you on the banking battlefield? What is your brand permission allowing you to do? Where do you start? Boldy step forwards with a new brand to protect what you currently have or evolve the existing one?