Org design isn't a people chart, it's the foundation of a good company culture

Organisation design is essential in building a strong working culture. Getting it wrong can cause a domino effect of problems and inefficiencies across a business.

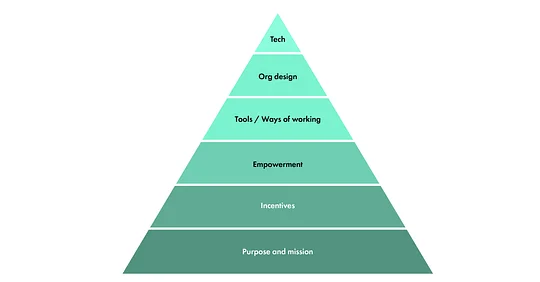

When we look at the 11:FS pyramid of culture (first introduced in our report - Rebuilding financial services from the inside), we see that the foundation to a strong working culture is purpose and mission. Without a clearly defined purpose, the operational tiers - org design, ways of working, empowerment, and incentives - are redundant, and the company is trapped in organisational stasis. Even today, this is not a popularly accepted fact. A lot of companies focus most of their attention on technology, which is just the tip of the iceberg - or pyramid. Tech is important, but only reaches its full potential with the support of the foundational layers beneath it.

Organisation design is not just a map of who manages which team members - it's a strategy for how communication flows. It's central to supporting the goals of the business and building and maintaining a strong working culture.

it's a strategy for how communication flows.

A short history of organisation design

At the start of the 20th century, the prevalent organisational model began in industrial manufacturing with the model of the organisation as a machine. In this model, workers are components (or resources). Most machine components are easily replaceable. A small number of components are responsible for controlling the machine; these are much harder to replace. As a result, a hierarchical model emerges as the dominant organisational paradigm. Managers are at the top, factory floor workers are at the bottom. Management is viewed as skilled, whereas production work is not. Pay and incentives align accordingly.

A large number of organisations began to apply this model to knowledge work. ‘Command and control’ became ‘predict and control’; managers and employees were given targets to achieve; new departments were formed, including Research & Development, Marketing, Product Management etc. Meanwhile, central functions including Finance and IT become very prominent in large organisations.

Where industrial organisations had one hierarchy, we now have one per function. This is known as functional hierarchy.

Problems with functional hierarchy: trapped in silos

Functional hierarchy has its share of problems. One of the main issues is how to structure collaboration across functions. In any service organisation - especially those that deliver their products through digital channels - individuals with specialised knowledge need to collaborate in order to meet customer needs. In this model, that is difficult to achieve. Each skill set is stuck in a functional silo, working on priorities set by the management of that silo. How do you rectify this?

The easier part is getting the functional managers ‘out of the way’ - removing them from decision-making at the tactical or production level of the organisation. This reduces micro-management and empowers front-line employees. Top and middle managers are effectively asked to share power and give up some control. This dynamic recognises that people at the ‘bottom’ in knowledge work organisations are just as skilled as managers, but in a different domain.

The harder part is how to actually structure the collaboration between functions. Despite considerable distance from our industrial beginnings, we still have hierarchical structures. In more mature organisations, they now represent a separation between strategic decision-making (those at the top) and tactical decision-making (those at the bottom), with experts at all levels. However, the fundamental structure is unchanged.

So what does ‘good culture’ look like and how do I get there?

Organisations with good culture are built on motivation. As an Agile Coach, I think about this a lot. I am a big advocate of Daniel Pink’s model, which suggests there are three key components to inspiring motivation:

Autonomy: people feel trusted to take ownership of their work

Mastery: people are given the tools they need to continue to improve their skills

Purpose: people believe in the “why” behind their work

In my view, successful organisation design is about creating an environment in which these attributes are maximised. The question, then, is how to actually do this?

Matrix management is one possible (yet flawed) solution. As with the functional structure, employees are grouped by specialism and report to a head of function. At the same time, they are embedded within multidisciplinary teams, and so report to someone ‘in the business’ as well as their functional manager.

My next post will analyse this in more depth, with a contrasting look at the divisional paradigm, and how well both models succeed at building a strong working culture.