Are you selling or partnering with banks?

The fintech ecosystem is currently going through an exciting phase. Startups that were once considered young and immature like Monzo, Revolut, or Airwallex have grown into established financial companies. At the same time, incumbent banks are getting better at engaging and investing in fintech. The two worlds are converging and sparking new opportunities for partnerships.

These partnerships are crucial, particularly for startups. Fintechs need cost-effective distribution channels, with profitability as a key goal. On the other hand, banks often still struggle with internal innovation and fail to achieve results.

This is where partnerships can be valuable and when done right, partnerships are a symbiotic relationship where each party brings something unique to the table. Fintechs offer innovative technology while banks contribute with their large distribution networks and most importantly, with credibility. Despite the potential, successful case studies are rare with reports more often highlighting unsuccessful partnerships - see Bilt and Wells Fargo example.

In this article, we cover all the different types of partnerships that exist and the common challenges they present. In the coming weeks, we will follow up with a practical guide for fintechs that aims to alleviate some of these challenges which you can sign up to receive here, but before let’s clearly define what a partnership even is.

Am I selling or am I partnering?

There is quite a lot of confusion in the industry about what constitutes a partnership as opposed to a simple sale. It might seem like semantics, but using both terms interchangeably can be counterproductive. While a partnership almost always requires a selling process, not every sale can be called a partnership.

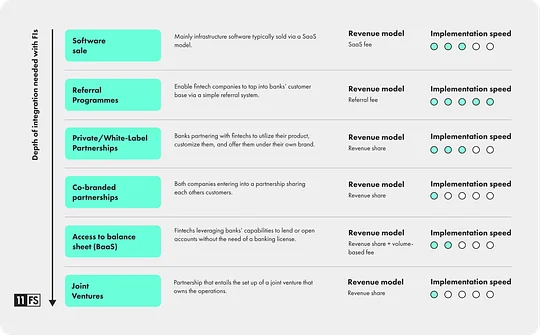

A partnership is an arrangement where both parties share responsibilities, liabilities, and profits. This isn’t the case if a fintech is just selling software to a bank - the fintech isn’t a partner, it’s just a vendor. A simple rule of thumb is if a bank is paying for a product or a service, it is a sale. Instead, when there is a form of revenue share or an effort to mutually offer a service, we are talking about a partnership.

Being clear about whether you are seeking a sale or a partnership with a bank is essential, especially when selling fintech. Both options have pros and cons, but selecting one over the other will largely shape your action plan and proposal to them.

Types of partnerships

Going one step deeper, not every partnership or sale is the same. Multiple methodologies can be applied. Here is a thoroughly incomplete list of potential partnership (or sale) types in a fintech context:

Referral Programmes

Referral programmes are one of the simplest forms of partnership. In this model, fintech companies can leverage the banks’ customer base, with banks referring their customers to the fintech service. Although referral programmes typically do not require deep technical integration, they still undergo extensive vetting processes to ensure banks feel confident referring their customers to a third party. More recently, financial institutions have launched so-called ‘ecosystems’ where they assemble a set of pre-vetted services that complement their product and that they directly recommend to their customers. This is a great distribution channel for fintech companies to tap into.

Example: JPMorgan’s Payments Partner Network is a great example of a bank creating an open ecosystem in which it integrates with various third-party providers like Modern Treasury or Primer. Via this solution, JPM expands its offering to its clients while referring new customers to third parties and fintechs.

Joint Ventures (JVs)

A joint venture between banks and fintechs comes closest to an equal and ‘pure partnership. Both partners have a vested interest in the venture and each carries responsibilities. These responsibilities are legally defined and a new legal entity (a JV) is formed to manage the operations of the partnership.

Example: In 2023, HSBC announced its plan to set up a JV with Tradeshift. Via the JV, they will jointly offer trade financing solutions. HSBC is also investing $35m into Tradeshift as part of the deal (source).

Co-branded Partnerships

Similar to a joint venture, a co-branded partnership involves a bank and fintech collaborating to develop a co-branded product or programme. This model allows banks to expand their product offerings while fintechs gain access to cost-effective distribution channels. Unlike joint ventures, co-branded partnerships do not necessarily require a legal JV setup, making them more flexible.

Example: Yokoy and UBS went into a co-branded partnership in 2022. The Swiss spend management software now offers co-branded business credit cards facilitated by UBS. It’s an interesting move that positions Yokoy not as a disruptor of the Swiss banking giant, but rather as a complementary service.

Access to balance sheet (BaaS)

One of the most common types of partnerships is fintechs partnering with banks to offer banking services to their customers, commonly referred to as banking-as-a-service. Fintechs can leverage banks’ capabilities to lend or open accounts without needing a banking licence. Banks, in turn, gain new customers and opportunities for lending or deposits at a lower cost.

Example: This is a vast topic with countless examples - like Bilts complicated partnership with Wells Fargo briefly mentioned earlier. UK banks are still catching up with the world of BaaS and are mainly interested in large deals. Yet there are API-first banks like Clearbank, Solaris, Griffin, and Natwest’s new upcoming venture “Natwest Boxed” that offer aggregated APIs to fintechs wanting to offer payments, accounts, or even lines of credit.

Private/White-Label Partnerships

In these partnerships, banks purchase or partner with fintechs to utilise the fintech’s product, customise it, and offer the productunder their own brand. Typically, this is more of a licensing arrangement than a true partnership, with banks licensing the technology directly from the fintech. However, in some models, the fintech also receives a percentage of the revenue.

Example: Dankse Bank worked with Backbase to revamp their digital banking apps. Instead of building the application from scratch, they were able to use Backbase’s platform to reduce costs. Backbase is a prime example of how to successfully partner and sell software to small-to mid-tier banks (source).

Infrastructure Software Sales

When solutions are not user-facing, they usually involve infrastructure software sold under a typical SaaS model. This type of sale, while standard, is far from straightforward. Selling software to banks is arguably one of the most challenging sales processes, possibly second only to selling to governments. Long sales cycles and complicated procurement processes make it hard for new entrants to compete with incumbents and legacy software solutions - more on that to come.

Example: Data warehousing and analytics powerhouse Databricks is a well-known name in the industry. It has sold its services to numerous financial institutions from newcomers like Nubanks to incumbents like Raiffeisen. Databricks, like many other large tech companies, cracked sales to banks with a great product and an armada of salespeople (source).

Each type of partnership has pros and cons, while referral programmes are easier to set up, they often need more results - especially for the fintechs expecting more leads. Instead, partnerships that require significant set-up time and consideration, like joint venture co-branded partnerships, can often result in great outcomes for both parties. Yet this is only achievable with a strong relationship that has to overcome many challenges.

Main partnership challenges

Conflicting motivation

The motivation and urgency behind going into a partnership are distinctively different for banks and fintechs. The latter often relies on partnerships to survive, so speed is critical. For banks, partnerships are often seen as a nice-to-have or an experiment, rather than critical. This difference in priority makes it difficult as one party is always pushing and the other seeks safety rather than speed.

Uncertainty about responsibilities

Partnerships that fail often do so because responsibilities, particularly around compliance, are not clearly defined. Uncertainty about responsibilities can lead to significant issues when multiple players come together. A recent prime example is the legal battle and blame game between Evolve and Synapse (source).

Unclear pricing or revenue share agreements

Setting clear pricing and revenue share agreements is challenging. As mentioned above, fintechs depend more heavily on the financial success of these partnerships than banks do, which puts them at a disadvantage in negotiations. Additionally, there are no standard market terms; each partnership has unique, often opaque, conditions.

Lack of clear sales channels

Approaching banks can be difficult, even when some institutions have appropriate partnership schemes and programmes. Identifying the right team or individuals to contact is challenging. Cold outreach rarely works, with most connections made through networks, warm introductions, or public RFPs.

Long procurement and POC processes

Even after you have found the right stakeholders inside the banks, getting budget sign-offs can take months. After getting the required sign-off, going through procurement is a challenge in itself. Most of the time fintechs will have to deal with RFPs and procurement teams that are tasked to assess potential risks and squeeze them on price.

Waiting for banks to change is hard. Most of the time it’s up to the startups to adopt a product and sales strategy that resonates with the traditional banking culture.

Conclusion

Beyond technical difficulties and long sales cycles, fintechs and banks have fundamentally different cultures and risk appetites. This cultural divide is the main challenge that needs to be addressed. Banks must become more agile and establish better internal partnership structures, while fintechs need to mature and adopt a more professional approach in how they sell and deal with banks.

Waiting for banks to change is hard. Most of the time it’s up to the startups to adopt a product and sales strategy that resonates with the traditional banking culture. This means hitting certain security standards, building risk mitigation plans, being patient and having realistic sales timelines, and most importantly, learning from companies that have been through it like the likes of Backbase, Thoughtmachine, and Databricks. These companies have cracked the code and their story can be followed and replicated by other fintechs.

What next?

As we've covered, this is a complex topic with a lot of nuance which is why this is just the first in a series of content pieces that will include practical guides for both financial institutions and fintechs on how to better prepare for and structure successful partnerships. If you'd like to be the first to receive these, you can sign up here and we'll send them over as soon as they're ready.

If you are a practitioner or a founder with experience working on fintech-bank partnerships please reach out, we would love to talk to you.